SPONSOR POST

By Jeff Edwards, General Manager, Global Gas & LNG Market Development, Royal Dutch Shell

Recently, I had the good fortune to join a round table discussion with a group of Japan’s leading thinkers on energy issues, hosted by National Geographic in Tokyo, in partnership with Shell. The discussion focused on the very real dilemmas that Japan’s decision makers face as they seek to navigate a new course for the country’s energy future. In many ways, Japan’s challenges are unique as it struggles to recover from the devastating Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011 and the resulting Fukushima nuclear accident. However, Japan also shares challenges with some other developed countries – a downward demographic trend in working population, densely populated but mature cities, and an economy struggling to overcome a period of protracted economic stagnation.

In energy terms, Japan also struggles with the same “trilemma” of issues that confront all developed countries – getting the balance right between competitiveness, environmental protection and energy security. The continued shutdown of most of its fleet of nuclear power facilities in the wake of the Fukushima incident has had a profound impact on all spokes of the ‘trilemma wheel’ and injected a clarifying sense of urgency into the national energy debate.

While Japan has struggled for the past two decades to regain the economic heights of its heyday in the 1980s, the external context for energy has fundamentally changed. New technologies– both the dispersion of renewable energy technologies and the impact of unconventional technologies on global gas supply – are reshaping the energy debate. At the same time, the climate change debate has taken on a new sense of urgency globally, an urgency reflected in the recent bilateral agreement between the United States and China on emissions reductions.

Throughout this tumultuous period, Japan has proven both resilient and resourceful. Faced with the shutdown of its nuclear capacity, the country relied upon its significant liquefied natural gas (LNG) import capacity and wide network of commercial relationships to keep the lights on. Japan suffered from power curtailments for some time after the Fukushima accident but quickly recovered enough to supply electricity even during peak seasons. Carbon dioxide emissions, however, have risen as the country has been forced to rely more upon fossil fuels to replace missing nuclear capacity.

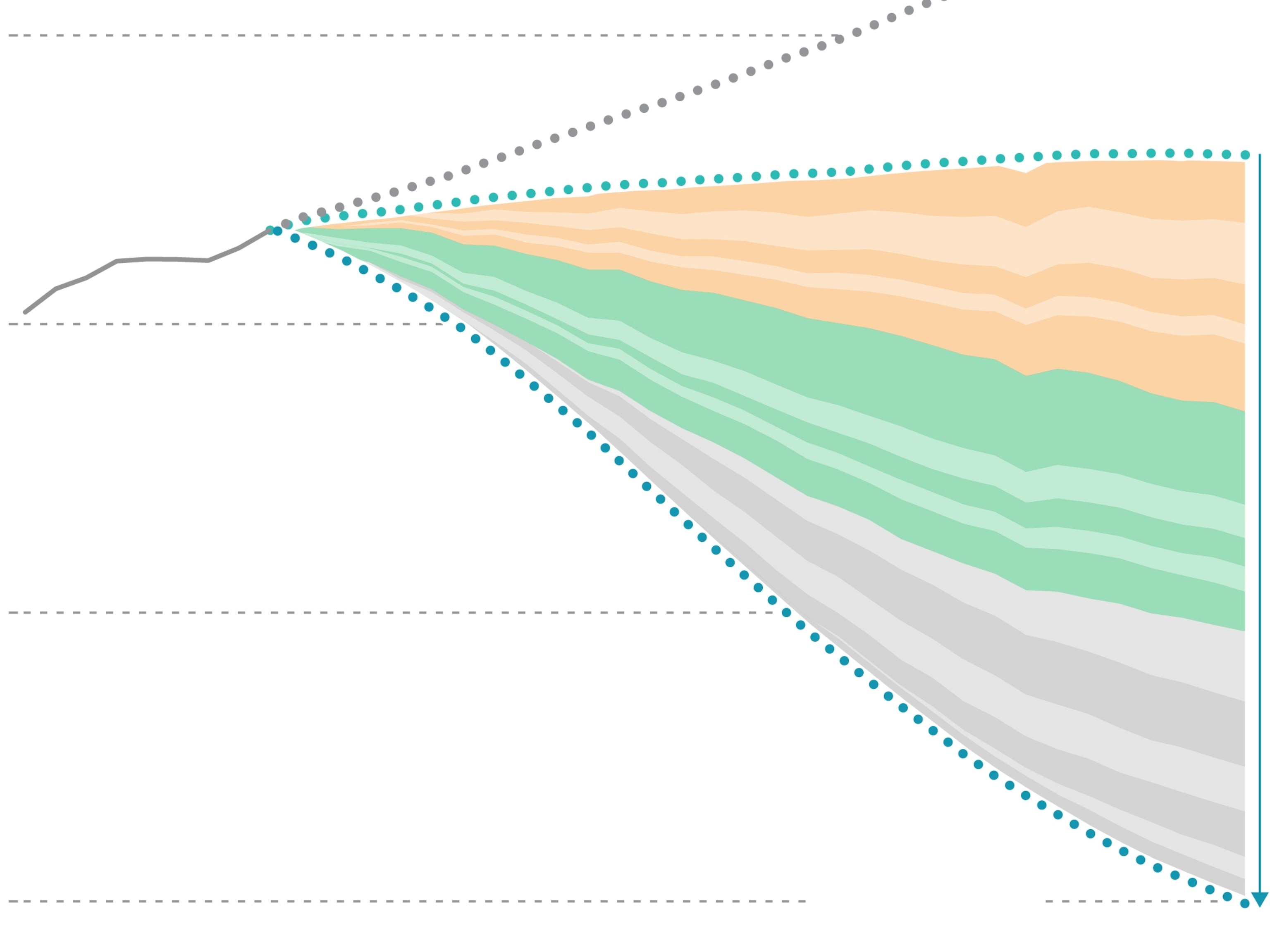

Looking forward, Japan will look to establish a more balanced energy system. The county plans to increase its deployment of renewable generation technologies toward a non-binding goal of achieving 20 percent of total generation from renewable sources by 2030 (from about 10 percent today). However, expanding Japan’s renewable generation sector faces challenges, including the need for new investments in expansion of transmission systems. Nuclear will still play a role, but the level of capacity that will come back online remains uncertain.

Given these uncertainties, Japan needs sources of energy which are both resilient and low carbon. Natural gas remains best positioned to play that role. Imported LNG provides energy security through increasing diversity of supply sources. In 2000, there were only 12 countries exporting LNG globally; by 2020, that number will have risen to 25. Gas-fired generation also provides superior system integration with renewables, as both start-up and ramp-up times for gas-fired generation are usually much faster than for conventional coal generation units. Such flexibility facilitates a smoother integration of renewables into the energy system. Gas utilized in power generation also releases up to 50 percent less CO2 than even the most advanced coal-fired generation technologies.

The flexibility and security that natural gas provides extends to distributed energy systems as well. The Roppongi Hills, where the event was held, is a complex of office buildings, hotels, and residential blocks powered by a natural gas trigeneration combined heat and power (CHP) unit supplying electricity, heating and cooling to the whole area via the grid and pipeline networks. In simple terms, CHP captures the waste heat produced during the electricity production process and uses it to heat water, or buildings, (as opposed to purchasing electricity and then burning fuel on site to produce thermal energy). Because it produces the electricity on site, it avoids the losses and costs associated with the transmission and distribution from a central power grid. In general, it is 16 percent more efficient than conventional forms of supply, and so consumes less fuel and produces fewer GHG emissions compared to other more CO2 intensive grid electricity sources. Japan has instalment capacity of about 5 gigawatts and such systems proved robust during times of earthquakes or major storms.

As the Japanese energy industry turns a page on its recent troubles, natural gas should maintain its critical role in the future energy mix. Gas has proven itself as the most dependable source of clean energy that best balances economic, environmental and security priorities. When combined with renewables, natural gas can provide a resilient, clean and flexible foundation for Japan’s new energy economy.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction