Wind, Sun and Water: Getting Past the Geography of Renewables

One of the interesting – and challenging – problems with energy policy is that it’s both global and local. The implications of climate change are worldwide, and so is the problem of meeting surging demand. And certain kinds of energy, like petroleum, are traded in truly global markets.

When it comes to electricity, however, what you get is the result of the fact that not every solution works in every place – or at least, not as well. This recently released map of hydropower use from the U.S. Energy Information Administration makes the point. Hydropower depends on whether you’ve got a river to dam, and whether you’re willing to dam it. So it’s no surprise that hydropower provides a huge amount of electricity in some states (more than 60 percent in Washington state, for example) and not much at all elsewhere.

But that’s true of electricity overall. Only a handful of power sources provide electricity in this country, and the source you rely on depends a lot on where you live. In New England, most power is coming from natural gas and nuclear power (Vermont gets three-quarters of its electricity from nuclear, and Massachusetts gets 60 percent from natural gas). In the Midwest, they’re mostly using coal (three-quarters of all the electricity in Kansas comes from coal plants).

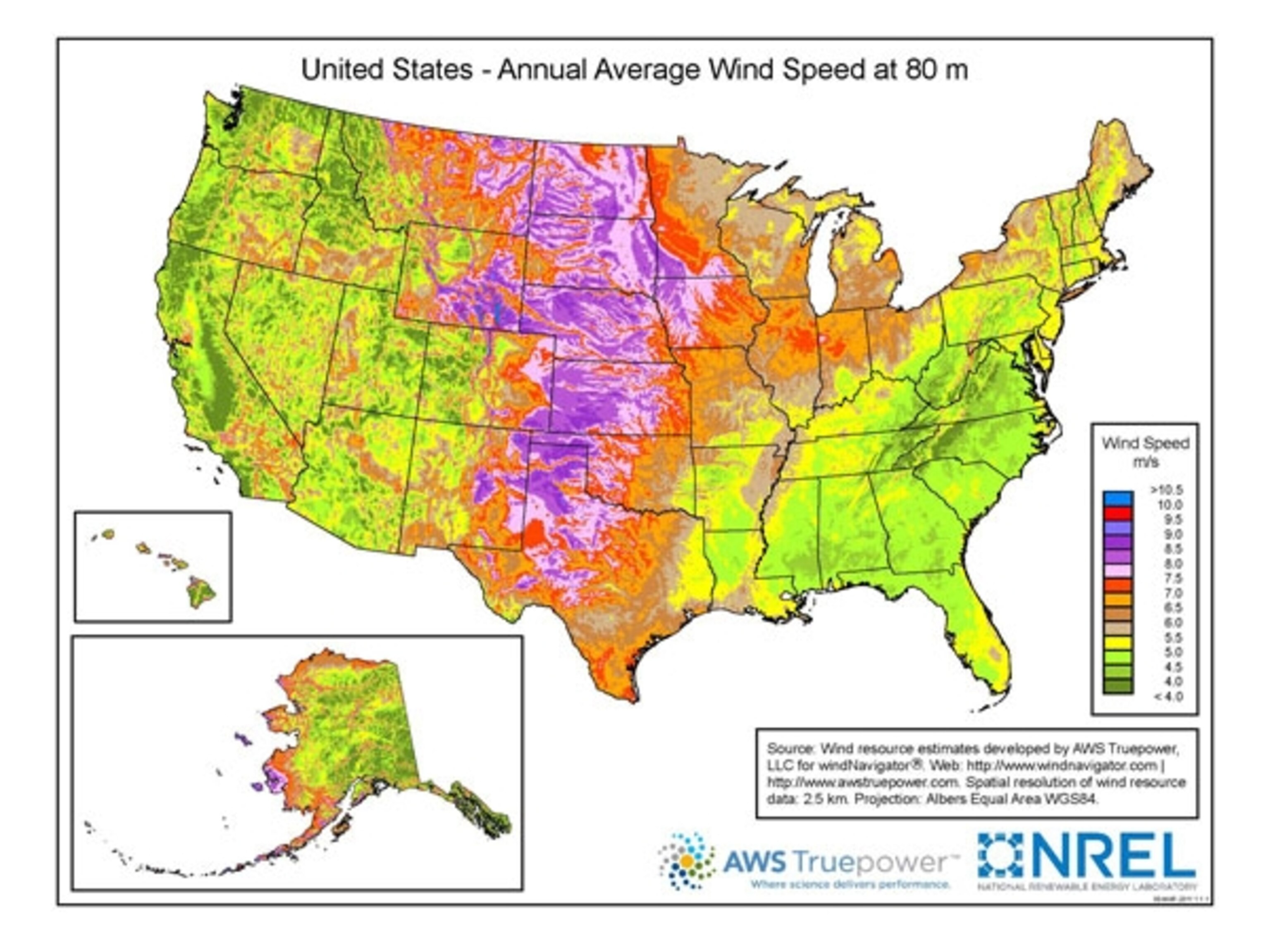

Even so, you can always replace one kind of conventional power plant with another (in fact there’s a long-term trend moving away from coal and toward natural gas). When we start talking about renewables, however, geography plays a crucial role. Certain parts of the country are just better suited to certain kinds of power. For example, have a look at this map of wind power potential from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory:

Wind turbines have to make the best possible use of geography, since the wind doesn’t blow at the same speed every day or at every height. When you look at the map, you can see why states like Texas and Minnesota are major players in wind-generated electricity, and other places may always be also-rans.

There’s a similar pattern with solar power. Nearly every place can make some use of it, but obviously it works best where it’s, well, sunny.

Geography may not be destiny, if we can get the power grid that we need. Right now our aging grid can’t ship electricity the distances it needs to go in order to allow wind power from the Great Plains to make it to major cities, or to deal with the peaks and valleys of production caused by weather. It’s just another reason why we need to make investments in the grid – not just to replace equipment that’s wearing out, but to make the most out of new opportunities.

With proper support, renewables could change the energy landscape, even if they’re still dependent on the landscape that produces them.

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital